Degrees of Clean

Why Clean Sales is a ladder, not a switch — and how to climb it

Published: August 18, 2025

In Outbound is Dirty, I compared conventional outbound sales to a poorly regulated factory: profitable for the operator, costly for everyone else. The costs take the form of an attention tax, minutes of focus taken from unwilling recipients of poorly targeted emails. These recipients are, in effect, subsidising the sender’s business.

I cast the problem as a binary: your outbound is either “dirty” or “clean.” It was a convenient simplification, but reality is less tidy. Cleanliness is not a switch you flip. It is a ladder you climb, one rung or one step at a time. Some systems burn dirtier than others. The intelligent goal is not to reach some mythical top rung of perfect cleanliness, which would perhaps mean no selling at all. The goal is to keep climbing toward cleaner operation.

You can see the same pattern in energy generation. At the bottom step: wood fires, leaving soot on walls, clothes, and lungs. We climbed to coal: cleaner and more efficient than wood, but whole cities still wore a permanent gray coat. Then came natural gas: cleaner still, producing more heat per unit and at a lower cost, though still a fossil fuel with significant emissions, methane leakage during extraction, and reliance on finite reserves. Now we climb toward solar. Not perfect; it uses land, requires manufacturing, and recycling panels is a challenge. Yet it is vastly cleaner than anything below it and, in many cases, already cheaper.

Moving up the ladder usually means a better balance of cost and cleanliness. Some shifts are obvious. Solar beats coal on both measures. Others are harder to call. Old fuels can linger through habit, inertia, and sunk costs, even when cleaner, cheaper options exist.

Sales has its own version of the ladder. The bottom steps are mass-blast, low-precision, low-value tactics. Higher up are systems that aim precisely, deliver genuine value per touch, and know when to stop. They are cleaner and they work better. Yet, as in energy, the lower steps still dominate the grid.

Why Bother Climbing

One reason to climb is sustainability.

Hannah Ritchie, in Not the End of the World, defines it as meeting the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet theirs. For most of history, we failed at the first part: we could not meet our own needs. Now we can. But we do it by consuming the very systems that future generations will rely on.

Sales faces the same structural flaw. A company can meet this quarter’s target through mass outreach, misaligned pitches, and brute-force persistence. The tactic works, but only by degrading the channel itself — burning trust, lowering response rates, and making the next prospect that much harder to reach. It’s the sales equivalent of strip-mining: the numbers look great today, but you’re standing in a field of churned mud wondering where the next vein is.

Ritchie’s argument is that our generation is the first with the means to break this pattern. The parallel in sales is exact. We have the measurement to see the damage, and the tools to reduce it without reducing results. The question is no longer whether it can be done, but whether we choose to keep digging holes or start building something that lasts. (Spoiler alert: AI will help.)

Ways of Being Clean

Cleanliness isn’t binary, and it isn’t measured in only one way.

In energy, cleanliness is measured on several axes: carbon emissions, land use, deaths per terawatt-hour, toxic waste. Each is a separate measure of harm. Progress means reducing the impact on each axis, even if none can be brought to zero.

Sales has its own axes of cleanliness. Dirty systems impose the highest attention cost — consuming large amounts of human focus for little useful return. The goal is to meet sales targets while lowering that cost. Greater precision in targeting. Higher density of value in every contact. Messages that are clear. An approach that is honest and respectful. Improving on these dimensions reduces the cost imposed on the market and makes results more durable.

Precision: Aim Before You Fire

Dirty sales systems spray attention costs across people who were never going to buy. Precision reduces that waste.

I recently spoke with a sales rep selling an outbound tool. He proudly told me it delivered “industry-beating” reply rates of 5%. For every 5 people who responded, there were 95 who would rather not have received the email at all. That’s considered best in class.

The fix isn’t just “better lists.” It’s understanding why a prospect might be in-market now. In sales tech, this gets lumped under “intent signals,” but not all intent is equal. True intent is direct evidence of active interest or relevant need: a public statement from the buyer, a job posting that signals a capability gap, a technology change you know creates pain you can solve.

What often gets sold as “intent” is far weaker: someone at the company read a vaguely related article, or a contact clicked on a link in a generic newsletter. Those can help with prioritisation, but they’re not reasons to reach out. When your definition of intent is loose, you end up creating noise that drowns out the signal.

Precision means reserving the interruption for when you have a specific, time-sensitive reason to believe you can help. Every touch still spends attention, but when you fire only on true intent, the cost is far more likely to generate value — for you and for the buyer.

Value Density: Paying Back Attention

Once you’ve aimed correctly, the interaction must be worth the prospect’s time. Value Density is the ratio of insight delivered to attention consumed. In a clean system, that ratio is always in focus.

Consider a discovery call. In the low-density version, the seller works through a script. The buyer answers questions, the clock runs out, and they leave knowing nothing new. Thirty minutes gone — a pure attention tax.

In the high-density version, the seller arrives with context. They share observations from similar companies, highlight a risk the buyer hasn’t considered, suggest a quick check the team can run, or link a recent move to a likely consequence. The buyer leaves better informed, whether or not they are a fit.

Both calls meet the seller’s need for qualification. Only one repays the attention it costs.

Clarity: Don’t Make Them Pay Twice

Every message already costs attention. If it’s unclear, you add a second toll, the mental effort to figure out what you meant.

That second toll is rarely obvious, but the reader feels it. It’s that moment when they have to stop, re-read, and piece together your point. Even if they get there, you’ve made them work for something they didn’t ask for in the first place.

The empathetic move is to carry that burden yourself. Use their vocabulary, put the point first, make the next step obvious.

Honesty

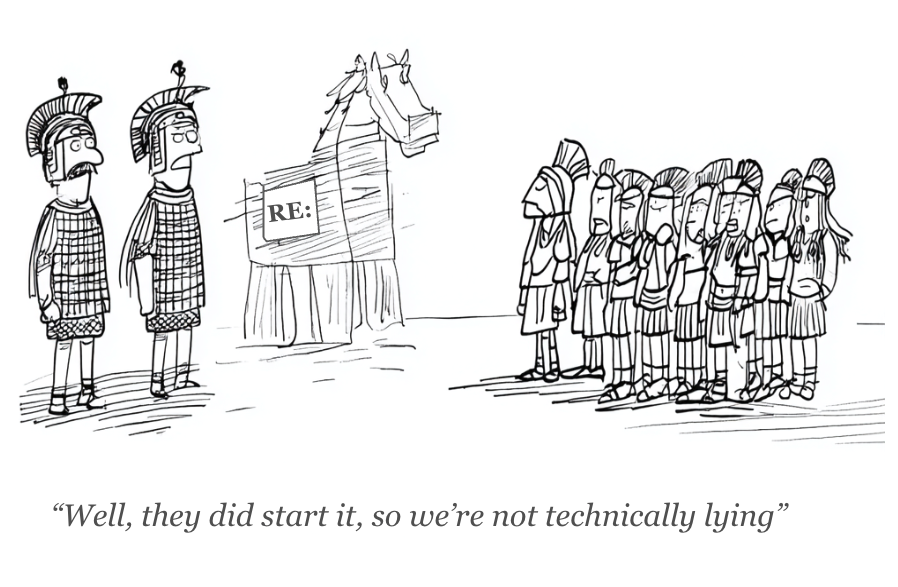

The fake email thread. Subject line starts with “RE:” to look like you’re replying to something they sent. You’re not. There’s no prior exchange.

Sadly, it works. Opens go up. Some people stay oblivious and a few even convert. But seriously — how do you look at yourself in the mirror?

Respect: Knowing When to Stop

No is no. It goes — should go — without saying. But if the prospect has to say it out loud, you weren’t listening.

If you want to see how deep the madness runs, Google “ideal number of touches in an email sequence¹.” You’ll find entire articles explaining why the “sweet spot” is somewhere between five and eight touches. Fewer than that and you’re “giving up too early.” Most replies, we’re told, come from later touches. That might be optimal if your only metric is overall reply rate. It’s far less optimal if you care about the attention tax you impose on society, let alone reputational costs.

I think even three is pushing it, even when I’m convinced the person would benefit from hearing from me. Every time an email is ignored is another clue the recipient doesn’t give a shit — so why keep pressing?

¹ There’s a whole industry of tools that will happily automate this for you — which is basically adding insult to injury, because the sender isn’t even taking the time to notice, let alone care, that you’re not interested.

The Work

If climbing this ladder feels like a lot of work, that’s because it is.

Dirty sales is easy. It’s the path of least resistance — a system optimised for the sender’s convenience. A numbers game played with other people’s time.

Clean sales is harder. It asks for thought, discipline, and real effort. But that effort isn’t a cost; it’s a signal. It says you respect the person on the other end. That you see them as a potential partner, not just an entry in your CRM. It is, in short, an act of empathy.

And the work pays. The return isn’t just feeling good about yourself; it’s a business that lasts. Sustainable results. A brand that survives the next quarter. A profession that pulls in great people instead of chewing them up.

The lazy path will always be there, waiting. The better one won’t build itself.

(Alright, technically AI can do some of the heavy lifting. But saying that here ruins my whole “noble struggle” ending, so let’s just pretend I didn’t.)