Outbound is Dirty

Modern cold outbound sales is a dirty business. But it doesn't have to be.

Published: August 7, 2025

Sales, as a human occupation, is essential and fundamentally good. At its core, sales is about helping people discover, understand, and ultimately buy the products or solutions a company offers. The very fact that customers willingly complete these transactions is proof enough that these products deliver real value. Seen this way, sales acts as a lubricant, a catalyst: it shortens the gap between potential value—the promise of what the product could do—and realized value, which the customer experiences once they purchase and use it.

The world simply cannot function without sales.

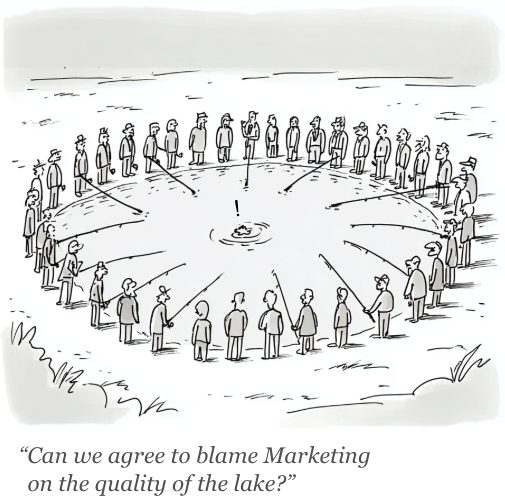

And yet, sales often ends up dirty, and cold outbound sales is particularly so. It generates pollution in the same way a chemical plant produces waste. To manufacture a profitable compound, the factory inevitably creates byproducts. When that waste is discharged into a river, the cost isn’t borne by the factory but passed downstream to communities living beside it.

Economists call this a negative externality: a cost imposed on third parties who neither chose nor benefit from the transaction.

Noise pollution is another example. A nightclub generates profit for its owners and entertainment for its customers, while neighbors—who didn’t vote for any of it—lie awake at 3 AM, robbed of sleep and peace of mind. Worse still, as they stare at the ceiling, they can’t help but picture the club owner raising a glass to a successful night.

Outbound sales creates similar negative externalities, ones I’ve always found hard to ignore when building sales operations. The pollution isn’t audible like noise or visible like waste, but it’s just as real. It appears as overflowing inboxes, interrupted conversations, and minutes stolen from our concentration. Individually, these costs seem trivial. But multiplied millions of times, they become a burden carried by society—imposed without consent or consultation, like those neighbors kept up by the nightclub.

Companies evaluate outbound programs using familiar metrics: the volume of outreach (emails, calls), conversion rates into qualified leads, and the percentage of those leads that become paying customers. Success is declared when the total value of closed deals exceeds the cost of running the program.

Those costs are typically calculated as the sum of data acquisition and validation, sales tooling (CRM, sequencing software, automation), outreach efforts (calls, emails, meetings), sales team compensation, marketing collateral, and, to a lesser extent, overhead like compliance and operations.

What’s never tallied in this equation are the costs outbound pushes onto everyone else. But if they were factored in—using the same cold numerical logic we apply to leads, deals, and returns—outbound might be designed very differently.

There’s another dynamic at play in cold outbound, one that mirrors a well-known dilemma from environmental science.

The tragedy of the commons, a concept popularized by ecologist Garrett Hardin in the 1960s, describes how shared resources tend to be overused when individuals act in their own immediate self-interest. In Hardin’s example, several shepherds graze animals on a common pasture; each benefits by adding more livestock, but the damage from overgrazing is shared by all. Eventually, the resource collapses—and everyone loses.

Sales faces a similar dynamic. The common pasture is customer attention. These are people who might genuinely benefit from our product, if we could just hold their interest for a few minutes. But that same customer lives in a swarm of competing offers, each salesperson acting rationally by sending one more email, making one more call, leaving one more message.

The result: an ecosystem choking on excess. Attention—once relatively abundant—has become scarce, expensive, and increasingly immune to capture, another casualty of a system that generates value by offloading its costs on time, focus, and consent at massive scale.

It doesn’t have to be this way.

The assumption that waste is an unavoidable byproduct of sales isn’t a law of nature. It’s a consequence of how we choose to operate: how we build teams, run programs, and measure success.

So: is it possible to build a truly Clean Outbound?

That’s the question I explore on these pages: whether outbound programs can be reimagined to drastically reduce the negative externalities we’ve come to accept as normal—and, just as critically, whether they can match or even outperform the effectiveness of the conventional, “dirty” systems that dominate today.

Because unless it delivers real results, Clean Outbound is just another elegant theory collecting dust.